“The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” remains Bunuel’s most successful film. It made more money than his famous “Belle de Jour” and it did manage to win Oscar as best Foreign language film. It was released in a year when Vietnam war was going in full form and the upper middle class was an obvious target of disdain. Bunuel worked in Mexico,Hollywood,Spain before again returning to Spain. He spent years in political, financial and artistic exile, and many of his Mexican films were done for hire, but he always managed to make them his own. His characters are often selfish and self-centered, willing to compromise any principle to get their job done.

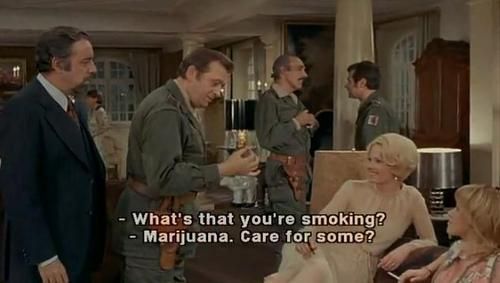

From the first shots of “Discreet Charm,” we are aware of the way his characters carry themselves. Fernando Rey stars as Don Rafael, the drug-dealing ambassador of a fictional Latin American country who lives in constant fear that one day he will be kidnapped and murdered by the guerilla terrorists outside his embassy. His friends repeatedly convene at the home of Monsieur Senechal (Jean-Pierre Cassel) and his wife, Alice (Stéphan Audran), whose dinners are constantly interrupted. The most amusing thing is that they never manage to dine properly. When the guests arrive for the dinner party, the hosts were having sex backyard. When the guests arrive at a restora to have dinner,they do hear that the owner is dead. Hearing this, they refuse to dine there and soon they leave the place. Elegant ladies sit down for an afternoon tea, only to be told by their waiter that the restaurant has run out of water.

Much of the film takes place in the nightmares of its characters. The protagonists seem to know what they want but they never reach their goal. They have all kinds of knowledge about manners and gestures, but they cannot sit down and eat. In Bunuel’s films, the clothes not only make the man, but are the man. Consider the bishop (Julien Bertheau), who arrives at the door in gardener’s clothes and is scornfully turned away, only to reappear in his clerical avatar to “explain himself,” and be accepted. Meanwhile, the narrative cuts in and out of dream sequences; at one point, one character’s dream turns out to be embedded in another’s. The text falls apart, so we find ourselves focused on the subtext. For all it’s symbols and destructing narrative, it is never a difficult film. Buñuel’s emphasis on the implacable dream logic that drives the film’s forking-paths storyline isn’t what you would call unprecedented. His films have often incorporated dream imagery, leaving even the most melodramatic material with outbursts of oneiric intensity. For the first-time Bunuel was provided with a video-playback monitor. The film employs meandering, unobtrusive camerawork and odd crane shots. There’s an elaborate tracking shot that follows one of the persons across the living room, up the staircase, and along the hallway. All of the performances were wonderful.

Even in the most dramatic scenes,they were never out of line. Special mention goes to Fernando Rey who was effortless throughout.